Page 5

The demise of the career of Stevedore Steve

He was at the height of his popularity. He was honoured by the Mayor of North Bay. He had trophies by the score, awards that filled a wall and fans in every part of Ontario and the Maritimes. Steve and Gini were on the road for weeks on end and it seemed that, from the outside, nothing could hold back his career. But there were things going on behind the scenes; after years of sniffing them out, I have had bits and pieces fall into my lap.

It was not just to Stevedore

Steve that things were happening; things were changing everywhere with

the advent of the mid-1970s. The Parti Quebecois was looming over the horizon;

Joe Clark was the new rising star of the Tories; the old Canada was being

transformed into the realm of the global village. Since the Centennial

bash in 1967, Canada was feeling quite grown up. Pierre Elliot Trudeau

was the first Canadian Prime Minister to offer us youth and vigour, hope

and belief in our national potential. Then the FLQ came and struck terror

into our hearts, the War Measures Act was used to round up innocent people.

And then we nearly lost the world hockey crown when the Russians came shooting

pucks in 1972. These things brought us a new sense of reality that was

a little hard to swallow.

With this kind of background

the Canadian music scene was shifting gears as well. With the new Canadian

Content rules and the Juno Awards in place we experienced a hyper-jump

in certain parts of the industry. In the trenches though things appeared

calm, much as they always had been. It was in the "Industry" that things

were happening at break-neck speed. Changes in structure, in tax laws,

in Canada Council grants were all happening within a short period of time.

The seediest sides of the business were no longer deemed acceptable: no

longer would unsigned contracts, unpaid royalties, ignoring artistic rights

be acceptable by the Canadian Recording Industry Association. It was necessary

to clean up the acts of those establishments who were obvious embarrassments.

With newer music companies taking advantage of the so-called plusses, it

was either adapt to change or falter.

The last real bastion of the old world ways of the Canadian music industry was the Country Music scene.

Winston 'Scotty' Fitzgerald, one of the greatest, most successful Cape Breton fiddlers to record, was in Toronto around that time; he asked to be driven to an address in Don Mills. He knocked at the door and went into the house for fifteen minutes before returning to his waiting car and announcing: "That's the first time I've ever been paid a royalty."1 He was given $500 by George I. Taylor, President and owner of Rodeo Records, parent company to the Banff and Celtic labels, as well as eastern Canadian distributor of Aragon Records of Vancouver. Scotty had recorded albums for the Celtic label in the 1950s and early 60s, many having been sold in Scotland and throughout Canada.

Things got so bad that Cape Breton fiddlers - many of whom had recorded for Rodeo - stopped recording altogether from about 1965. One of them was Dan Joe MacInnis:

Coupled with the sleeve design, the distribution and marketing of the material were also managed by the recording companies, as was the case with the early 78's, and Dan Joe accepted this practice as the acceptable way to do business. Despite the fact that the new vinyl format was more durable and user-friendly, Dan Joe was not enticed to become personally involved in the marketing aspect which would allow him to distribute some LP's, at least locally, so that he could realize some share of the profits from sales. In summary, the only aspect of the recording which involved Dan Joe was his actual performance of the music - everything else was left for the exploitation by the recording industry itself. Dan Joe simply did not ask questions about the business side of this enterprise, and that was fine with the industry representatives! 2It seems that the prestige of having a recording issued on a major label, being able to receive some airplay on the radio, was enough to entice most artists to record. Eventually the Cape Breton artists started to realize that they were being duped by these companies, that their handshake contracts were a one way street. Sheldon MacInnis explains in his book:

By 1965, Dan Joe, like other fiddlers, began to lose interest in the recording studio, probably because of his busy performing schedule of concerts and dances, which consumed much of his time and provided him with a great deal of satisfaction; the negative experiences surrounded the use of person recorders; and the lack of monetary return from commercial recording industry. This caused a dislike and even mistrust of the recording industry by many fiddlers who had recorded earlier.3Mac Beattie, bandleader for the Ottawa Valley Melodiers, who composed many of the songs recorded by the group on its 11 albums during its 30 year career, was only ever paid 2 cents a copy for every album sold. He never received mechanical or public performance royalties until after his death in 1982. Again it was George I Taylor of Rodeo Records who held out. Somehow he had managed to get his hands on Beattie's public performance royalties, something that he was not entitled to. Through fancy bookkeeping mechanics, many of the artists were lead to believe that they actually owed the record company money.

"It was a joke," explained Mac's wife, Marie Beattie. "Oh, I remember the last time Mac and I had dinner with Taylor; they were busy discussing Mac's next album and when I asked where Mac's royalties were I got a swift kick in the leg under the table and a nasty glare (from Mac). He didn't want me to jeopardize his recording career. I used to get so mad at Mac! He'd tell me that he was well aware of the fact that Taylor was ripping him off, but when it came time to confront him about it, he'd just back off." 4

Mac

Beattie was acutely aware of the fact that as an ageing country music act

he would have great difficulty getting any kind of recording deal elsewhere.

(Mac Beattie, 1980, courtesy Marie Beattie)

I looked up some of the contracts signed by artists with Rodeo Records in the offices of Holborne Distribution who purchased the Rodeo catalogue just before Taylor died in the early 1980s. The one page documents had no dates, no terms, no publishing deals, no managerial deals and no end. They simply stated that so-and-so has entered into a recording agreement with Rodeo Records, signed (by the artist and George I. Taylor) without witnesses. After Mac Beattie's death, an autobiography which contained some poorly made sheet music was self-published by the family.

Marie Beattie: "He (Taylor) claimed that I had to give him a cut because he owned the publishing."

Marie persisted. Mac was gone now and Taylor would have to deal with her. When she cornered Taylor about a compilation album he had released without permission of the artists (The Saga of Canadian Country and Folk Music) he claimed that it was just a promotional album, that none of them were in the stores. When she purchased one in Ottawa she kept the receipt sealed in the white plastic bag as proof that the albums were being sold for profit. Taylor backed off and allowed her to publish the book. He also signed over all of Mac's publishing rights.

Interestingly enough, Holborne still distributes recordings by Rodeo Records artists, many of which have been re-released on CDs and Cassettes based on the contracts signed by these artists who lacked professional guidance and council, who knew nothing about the kinds of deals they were entering, and nothing about myriad royalties to consider.

Rodeo is only one example of what was the practised norm in the music business at the time. Examples of rip-offs ring through the most sacred halls of the recording industry world-wide. Executives were quick to pounce on un-suspecting musicians. Arc Records, Marathon, Condor, Aragon and others, including some of the more reputable major labels, were all guilty to some degree of this sinister activity.

But Boot Records was supposed to be different. This was supposed to be a label for and about Canadian music.

When Stevedore Steve signed with Boot, he signed up with friends. Little attention was paid to the language of the recording contract, and certainly there was no mention of who was responsible for what. Did signing a recording deal automatically mean that you were also signed to a publishing deal with another company? Was this also a managerial deal? Was there any mention of how royalties were to be paid, how often and to whom? Was legal representation present at the signing of these deals?

Such was the state of affairs.

Stevedore Steve was luckier than most and escaped most of the madness. He was supposed to purchase albums from Boot Records to sell from the stage. But expenses were high and new tax laws were chasing him like a pack of wild dogs. He failed to pay his bills with Boot so they stopped sending him boxes of albums to sell which lead to bitter recriminations. Riding on the success of his first two Boot albums, he wanted to go back in and record another one but Krytiuk had other intentions. He spoke with Connors who championed The Stevedore, his friend, and they came up with an unusual solution: Instead of spending more money on a losing proposition, they came up with the idea of releasing Stevedore Steve's greatest hits.

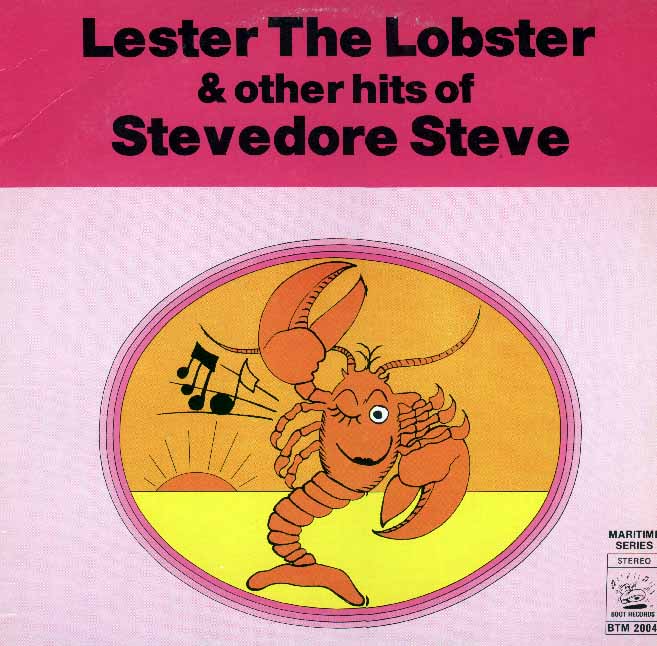

With

the release of his third Boot album, Lester The Lobster & Other

Hits of Stevedore Steve, the mighty Stevedore was flying high again.

(Even Connors didn't have a greatest hits album at the time.) From the

liner notes:

With

the release of his third Boot album, Lester The Lobster & Other

Hits of Stevedore Steve, the mighty Stevedore was flying high again.

(Even Connors didn't have a greatest hits album at the time.) From the

liner notes:

Then, in 1970 he toured Ontario. It was during this tour that he met record producer, Jury Krytiuk. This meeting led to a recording contract first with Dominion Records and then later with Krytiuk's Boot Records. It has been a fruitful relationship which has produced many national hit records including "Lester the Lobster" which hit the number one spot on the national country charts.5Meanwhile, Steve was on the road a non-stop. He was experiencing a lot of frustration and difficulty. He would travel to places that had no advanced copies of his records for local radio stations. If there was a music store in town, it would not have his albums in stock. If his private stock, purchased off the company for sales off the stage, was running low, he had a hell of a time replenishing it.

"I'd phone them, I'd tell them, 'By god, get me some albums man! People are crying for them and I'm all out.' But they just wouldn't send the damn things. I'd miss out on so many sales."

According to Connors: "He wasn't paying his bills. He asked us to send him records but he never paid for 'em."

Whatever the reason, Steve was getting very upset with the company. He thought that it must be some sort of conspiracy, that maybe the company didn't want him eclipsing the career of Connors, or even coming close. As far fetched as that might seem, in Steve and Gini's minds, while out on the road earning a living, it festered in a line of mercurial mistrust.

In 1977 Foote received a letter from Revenue Canada: they owed over $12,000 in back taxes. At first they thought it must be a computer error or something. How could they possibly owe the government that kind of money? It was about half of what they earned that year before expenses. Something was wrong.

Since they were constantly on the road, their van was packed with almost everything valuable to them: A PA system (still the property of Boot Records and never actually paid for by Foote), stage costumes, albums and even Steve's guitar. Since the Foote's could not pay their back taxes, their case was passed on to a collection agency who confiscated everything they owned except for the clothes on their backs.

"We just watched them take it all away," said Steve. "Everything. We said nothing and just as they were about to leave, I said to one of them that my guitar was my bread and butter. He winked and said, "What guitar?" and I said, "Why that's pretty good of you fella." 6

But for all intents and purposes, this was the beginning of the end of Stevedore Steve.

Notes

1. Sandy MacIntyre on the

Great North Wind radio program, Feb 11, 1998

2. A Journey In Celtic Music

Cape Breton Style - Sheldon MacInnis 1997, UCCB Press

3. A Journey In Celtic Music

Cape Breton Style - Sheldon MacInnis 1997, UCCB Press

4. Conversations with Marie

Beattie by Steve Fruitman, circa 1994

5. Liner notes of Lester

The Lobster & Other Hits of Stevedore Steve, Boot Records BTM 2004

1976

6. From a CBC Television

feature, On The Road Again, profile on Stevedore Steve, April 1996

Back to the Index

To go read about the missing years of

the career of Stevedore Steve, click HERE

© 1999 & 2010 by

Steve Fruitman for Back To The Sugar Camp ®